Wes Anderson has long been the cinematic equivalent of an eccentric watchmaker. Every frame was precisely engineered, every movement perfectly timed, every emotion tightly controlled beneath layers of pastel hues and deadpan line delivery. But as with any timepiece that never changes, there’s a risk it stops telling us anything meaningful. “The Phoenician Scheme”, Anderson’s latest diorama of ornate dysfunction, is another polished entry in a filmography that increasingly feels like it’s running in place.

I’ll admit—I find Anderson’s work hit or miss. When it hits (“Rushmore”, “Moonrise Kingdom”), it resonates with nostalgic melancholy and sly insight. When it misses (“The French Dispatch”, “Asteroid City”), it resembles a museum exhibit that nobody asked to be interactive. “The Phoenician Scheme”, unfortunately, falls into the latter category. It’s a film that looks great in a still image but collapses under the weight of its design the moment it tries to move.

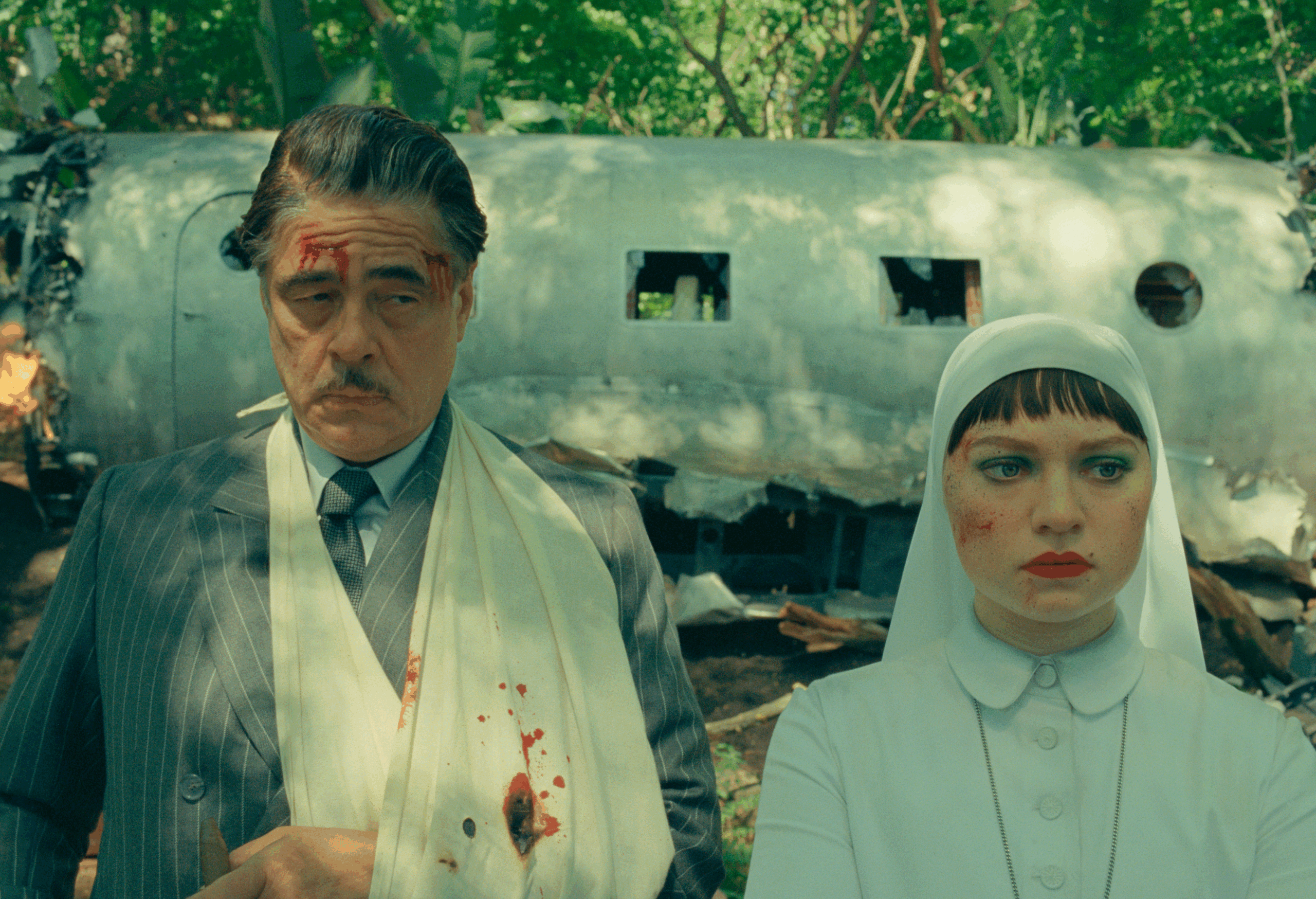

Set in an alternate 1950s, the story follows tycoon Korda (Benicio del Toro), who survives yet another assassination attempt. Instead of retreating, he leans into ambition, launching what he calls The Phoenician Scheme—a plan to acquire and exploit a region called Phoenicia for financial gain. Before doing so, he reunites with his estranged daughter, Liesel (Mia Threapleton), a soon-to-be nun who agrees to accompany him in exchange for some closure. Also along for the ride is Bjorn (Michael Cera), a socially awkward science tutor with questionable boundaries.

As the trio travels through a vaguely sketched “dangerous region,” the film becomes a series of highly stylized set pieces, each featuring a different celebrity in a neatly arranged cameo: Riz Ahmed as Prince Farouk, Tom Hanks and Bryan Cranston as shady power players, Scarlett Johansson, Benedict Cumberbatch, Mathieu Amalric—you get the picture.

These meetings are fewer scenes than framed vignettes, each immaculately dressed but dramatically weightless. There are attempts at humor, half-formed philosophical exchanges, and the occasional hint of emotional longing, but they all evaporate in the air, like perfume on marble.

Anderson’s obsession with symmetry and artificiality has rarely felt more oppressive. His camera never lingers where it might find something real—in one moment, a fight erupts offscreen, but instead of showing it, he focuses on the now-empty room, pristine and untouched. In another, a servant’s head is cut out of the frame entirely, all so Anderson can keep the geometry of a tableau intact. It’s hard to tell whether he’s commenting on power dynamics or decorating around them.

“The Phoenician Scheme” is tragic not for its incoherence but for its lack of curiosity. The film presents themes of capitalism, identity, and estrangement as mere backdrops rather than exploring them. Liesel’s doubt about Korda being her father could have offered an emotional anchor but is barely touched upon. Assassination attempts feel unimportant, and Korda’s con—exploiting a fictional nation—serves as another way for Anderson to display symmetrical architecture in a desert.

Despite its artful staging, the film lacks urgency. Anderson appears satisfied with repeating motifs that have become stale, making “The Phoenician Scheme” a freeze-frame rather than a progression. While beautiful, it resembles a snow globe—captivating at first but ultimately disconnected from a deeper experience.

Final Grade: C

“The Phoenician Scheme” opens in select theatres (NY/LA) today and will go nationwide on June 6, 2025.